Have you ever felt overwhelmed by the intricate rules of client trust accounting in California? Do you worry that a small mistake in handling client funds could jeopardize your law license or firm’s reputation? For small and mid-sized law firms in the Golden State, trust accounting is an unavoidable responsibility – and one that is highly regulated by the State Bar of California. In fact, mismanagement of client trust funds has historically accounted for about 12% of all State Bar disciplinary complaints. The good news is that with the right knowledge and tools, even a modest-sized firm can manage trust accounts confidently and stay in compliance with California’s strict requirements.

In this guide, we’ll break down California-specific trust accounting rules (such as State Bar Rule 1.15 and new regulations from the Client Trust Account Protection Program) and offer practical tips for law firm administrators and attorneys. You’ll learn the essentials of setting up and maintaining client trust accounts, avoiding common pitfalls, and leveraging legal tech solutions to streamline trust accounting. Trust accounting doesn’t have to be a headache – with some smart practices (and technology like LeanLaw), you can protect your clients’ funds and your firm with ease.

Understanding Trust Accounts in California

What is a client trust account? Simply put, it’s a separate bank account used to hold funds belonging to clients (or third parties) that a lawyer is temporarily in charge of. These funds might be advance fee retainers for future services, settlement monies awaiting distribution, court filing fees a client advanced, or any other client funds not yet earned or disbursed. Crucially, a trust account is not the law firm’s operating account – it holds clients’ money, not the firm’s. By law, this money must be safeguarded and kept separate from the firm’s own funds at all times.

IOLTA vs. individual trust accounts. California attorneys typically use two types of trust accounts:

IOLTA (Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Account)

This is a pooled trust account for client funds that are nominal in amount or held for a short duration. In an IOLTA, multiple clients’ funds are commingled with each other (with detailed records for each client’s share), and any interest earned on the account is sent to the State Bar to fund legal aid programs, not to the clients.

IOLTA accounts are used when it’s not practical to set up a separate account for a small or short-term client deposit – for example, a few hundred dollars to be held briefly. California requires that IOLTA accounts be held at approved financial institutions that pay favorable interest rates and agree to report any overdrafts to the Bar. The State Bar maintains a list of eligible banks for IOLTA accounts.

Individual Client Trust Account (CTA)

If you’re holding a large amount of money or holding funds for a long period for a client, you should place those funds in a separate, interest-bearing trust account for that client’s benefit (The lawyer’s guide to client trust accounts in California – One Legal). In such cases, interest earned goes to the client (since the amount/time justifies tracking interest for that client). Often, this might be a segregated savings or escrow account labeled with the client or matter name. For example, a personal injury attorney holding a six-figure settlement for a client during an extended appeals process should use a dedicated account so that the client will receive the interest accrual.

Whether it’s an IOLTA or an individual client trust account, the account must be clearly labeled as “Trust Account,” “Client Trust Account,” or “Client Funds Account” to distinguish it from any firm operating accounts. It’s also a best practice (and effectively required) to use a bank in California that is familiar with attorney trust accounts and the overdraft reporting rules.

Who needs a trust account? In California, any attorney who handles client money (beyond a minimal amount for a minimal time) must have a trust account. Even solo practitioners and small firms are not exempt – if you take a retainer or advance fees, you are holding client funds. The State Bar of California expects you to deposit those funds in a trust account until they are earned or disbursed. Even unearned flat fees or advances for costs generally belong in trust, unless they’re deemed a “true retainer” under the rules. The bottom line: if you ever find yourself saying “I’ll hold the money in trust,” you need to set up a proper trust bank account first.

Key California Trust Accounting Rules and Requirements

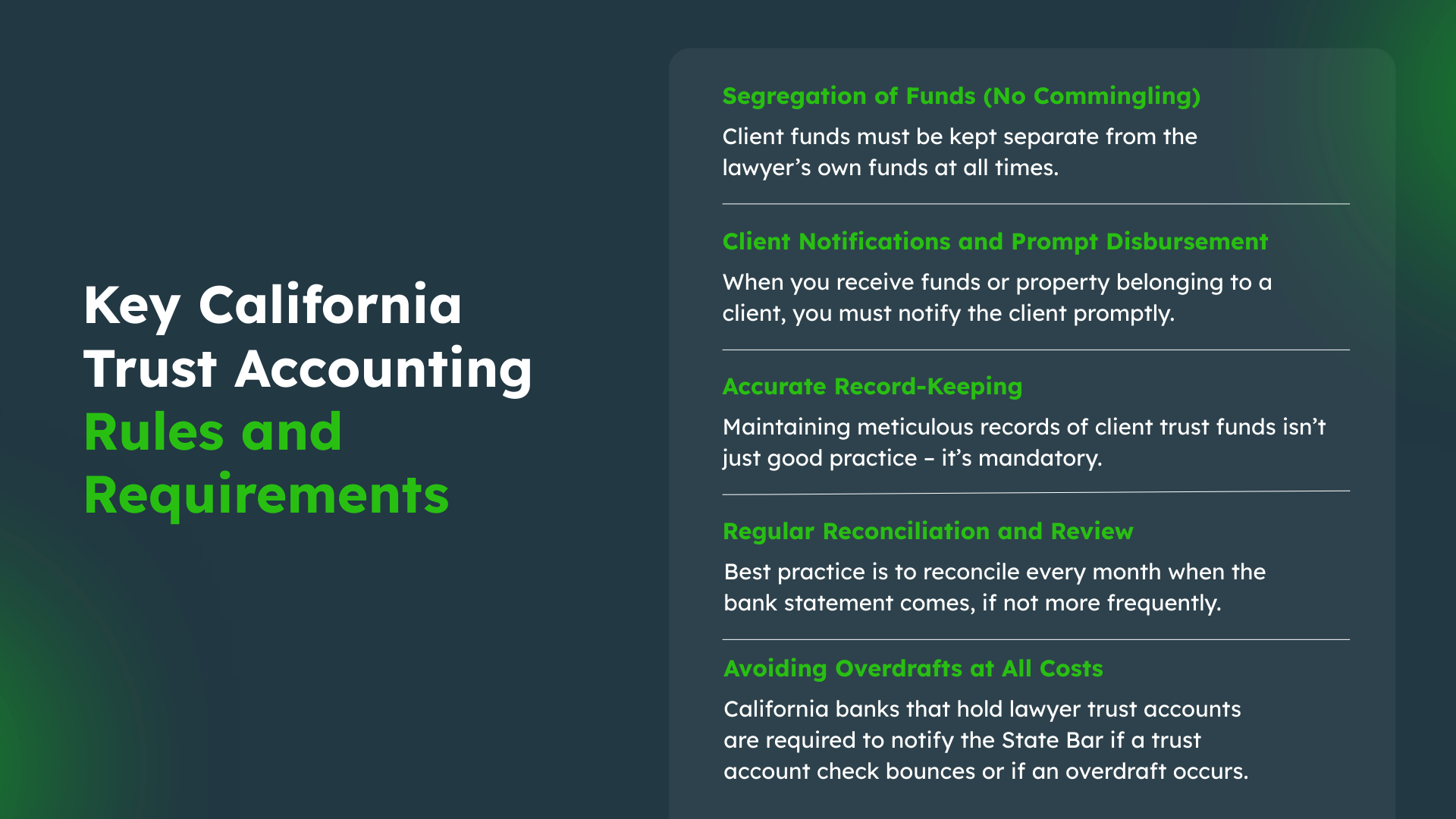

California’s rules on trust funds are among the most detailed in the nation. Rule 1.15 of the California Rules of Professional Conduct (adopted in 2018, replacing former Rule 4-100) lays out the ground rules for safekeeping client money. Additionally, new State Bar programs and state laws impose further duties. Here are the core requirements your firm must follow:

Segregation of Funds (No Commingling)

Client funds must be kept separate from the lawyer’s own funds at all times. You cannot deposit client money into your business or personal account. Likewise, you shouldn’t keep your own money in a client trust account, except in one narrow situation: you may deposit a small amount of firm funds solely to cover bank service charges if necessary.

Any funds belonging in part to the client and in part to the attorney (for example, a settlement check that includes reimbursement of costs you advanced) should be split and the attorney portion withdrawn to the operating account at the earliest reasonable time once it’s determined.

Tip

Avoid letting earned fees linger in trust – if you’ve earned it and billed it, transfer it out to the firm account promptly, or else it’s technically commingling. Conversely, never use client trust money to pay firm expenses – that’s conversion. Commingling or misusing client funds is a serious ethical violation that almost always leads to discipline.

Client Notifications and Prompt Disbursement

California’s rules put a big emphasis on prompt communication and delivery of funds. When you receive funds or property belonging to a client, you must notify the client promptly. Recent updates to Rule 1.15 (in the wake of the Girardi scandal) have made this even stricter – attorneys now have 14 days to notify a client or third party that you’ve received their funds. Moreover, you must promptly disburse or distribute funds to which the client is entitled. If there’s an undue delay in disbursing client money, the rules presume something’s wrong.

In fact, failure to pay out funds within 45 days of receiving them is now presumed to be not prompt unless you have a justified reason. For example, if you’re holding settlement proceeds, you should not sit on them for months – cut the client their check (and handle any liens) as soon as practicable. Similarly, if a representation ends, any unearned fees must be refunded promptly (per Rule 1.16 and Rule 1.15, as well as California Business & Professions Code §6091).

California explicitly requires in Rule 1.15 that an attorney remove earned fees from the trust account at the earliest reasonable time to avoid commingling, and Rule 3-700(D)(2) (old numbering) mandates prompt refund of any advance fee that wasn’t earned. The key principle: client money belongs to the client – you must notify, account, and deliver that money expediently.

Accurate Record-Keeping

Maintaining meticulous records of client trust funds isn’t just good practice – it’s mandatory. California requires attorneys to keep complete records of all funds held in trust and to preserve those records for at least five years after final distribution (per Rule 1.15 and State Bar Act provisions). What does this entail? At minimum, for each client trust account you should maintain:

- A ledger for each client or matter, showing all receipts, disbursements, and the current balance for that client. (If you have a pooled IOLTA, this is critical so you know exactly how much of the pooled balance belongs to each client at any time.)

- A journal (register) for the trust account as a whole, showing a running list of all transactions in and out of the account (like a checkbook register for the trust account).

- Receipts and disbursements records (e.g. copies of deposit slips, wire transfer confirmations, canceled checks or check register, etc.) for every transaction.

- Monthly reconciliation reports, comparing the bank statement balance to the sum of all client ledger balances and the account journal balance. This is often called a three-way reconciliation – the bank balance, the total of individual client balances, and your internal trust ledger should all match. Any differences must be investigated and resolved immediately.

Additionally, keep supporting documentation for trust transactions, such as copies of client instructions, settlement statements, or invoices that justify a withdrawal. California’s Rule 1.15 and Business & Professions Code §6091 give clients the right to request an accounting of their trust money at any time, and you must be able to promptly produce these records if a client (or the Bar) asks. Failing to maintain or produce proper trust records is itself a disciplinable offense and under the new rules, “must” result in the lawyer being enrolled inactive (i.e. suspended) until compliance is achieved.

Regular Reconciliation and Review

It’s not enough to just keep records – you have to actively reconcile and review your trust account often. Best practice is to reconcile every month when the bank statement comes, if not more frequently. In fact, the State Bar has made it clear that monthly reconciliation is expected. For many firms, a good routine is to reconcile the trust account at the same time you do monthly billing: this ensures that any client who was billed and had trust funds applied can be verified, and any discrepancies are caught before too much time passes.

If your firm doesn’t bill monthly (e.g. contingency fee practices), you should still set a recurring monthly task to reconcile the trust account. Some practice areas handling large client funds (like personal injury settlements) might even reconcile daily or weekly during active periods – the point is to keep a very tight handle on the trust balance so that mistakes or unauthorized transactions are caught immediately.

California also requires you to review the balance for each client: you should always know exactly how much you hold for each client, and the total of all client balances must equal the bank account balance. This three-way check is the gold standard of trust accounting. If you discover any error (for instance, a bank error or a posting mistake), correct it promptly and document what happened.

Avoiding Overdrafts at All Costs

One absolute rule of trust accounting is don’t overdraft the account. Spending even one dollar more than the available client funds is effectively using one client’s money for another purpose, and it triggers an automatic red flag. California banks that hold lawyer trust accounts are required to notify the State Bar if a trust account check bounces or if an overdraft occurs.

This means if you accidentally write a check that exceeds the client’s balance (or the account as a whole) – even due to a banking error or a delayed deposit – the Bar will likely find out. An overdraft inquiry from the Bar can lead to an audit of your trust records. To prevent this, stay on top of your balances.

Never assume a deposit has cleared; verify funds are in the account before disbursing. It’s wise to maintain a cushion (with your own funds, up to the amount needed for bank fees) in the account so that bank charges don’t accidentally overdraft the account. Many attorneys also set up alerts with their bank for low balances or check-clearing notifications. Remember, even the appearance of using one client’s money for another’s obligations is a serious breach of fiduciary duty.

Additional California Requirements

California’s trust accounting regime has a few extra wrinkles to be aware of. For example, when an attorney-client relationship ends, not only must you promptly return any remaining client funds, but any unearned advanced fees (minus any true retainer) must be refunded without delay.

Also, if a client gives you money to pay third parties (e.g. an expert’s fee), you must handle it as trust money and pay it out for that purpose – or return it to the client if not used. You cannot borrow from client funds, even if you intend to pay it back. And importantly, the duty to account and safeguard is non-delegable: even if you have a bookkeeper or office manager maintaining the ledgers, the attorney is responsible for any errors or misconduct in the trust account. The State Bar has disciplined attorneys who claimed ignorance because “my staff handled the trust account.” Don’t let that be you – always review the work and bank statements yourself.

Finally, be aware that mishandling trust funds carries severe consequences in California. The State Bar’s disciplinary guidelines call for stiff penalties whenever client funds are misused. In cases of intentional misappropriation, disbarment is the typical result. Even negligent mismanagement (with no client harm) can lead to suspension if records are sloppy or funds are at risk. In short, take trust accounting seriously – the State Bar certainly does.

The Client Trust Account Protection Program (CTAPP) in California

In addition to the longstanding rules above, California recently introduced a new program that directly affects all attorneys who handle trust funds. The Client Trust Account Protection Program (CTAPP), enacted in late 2022, is a regulatory initiative designed to ensure lawyers actively comply with trust accounting obligations. CTAPP is essentially a yearly check-up on your trust accounting practices, and it’s now a condition of maintaining your law license in California.

Under CTAPP, California attorneys must do three key things each year:

- Register all your client trust accounts with the State Bar annually. This includes IOLTA accounts and any non-IOLTA trust accounts. Even if your firm has one pooled IOLTA for all clients, you’ll need to report that. If you have separate client-specific trust accounts, those need to be reported too. The registration is done through your online State Bar profile and essentially informs the Bar where client funds are held.

- Complete an annual self-assessment of your trust accounting practices. The State Bar provides an online self-assessment questionnaire about trust accounting best practices. Attorneys must answer questions to gauge whether they understand and are following the required procedures (for example, maintaining ledgers, doing reconciliations, etc.). This self-assessment is meant to be educational, highlighting any areas where you might need improvement. But it’s also a compliance requirement – you must complete it each year.

- Certify your compliance with trust accounting rules. Finally, you have to certify to the State Bar that you have reviewed and understand the trust accounting rules and that you are in compliance. In essence, you are attesting that “Yes, I’m following all the rules in Rule 1.15 and related provisions.” This certification is a way of holding attorneys accountable on a regular basis, not just when there’s a problem.

CTAPP is a big change because it turns trust accounting into a proactive, reporting obligation rather than a reactive issue only investigated after a complaint. Starting with its first rollout, compliance has been strictly enforced. The State Bar initially set a deadline (for example, February 2023 for the first registration) and gave a grace period. But by mid-2023, the Bar took action against those who ignored the new rules. In July 2023, the Bar administratively suspended over 1,600 attorneys who failed to complete the CTAPP registration and certification on time.

Those attorneys were placed on “inactive” status – meaning they could not legally practice – until they fulfilled the requirements. The message is clear: if you don’t comply with CTAPP, you risk automatic suspension. The Bar has indicated that in future years the annual reporting deadline will be February 1, and attorneys who miss it will be promptly placed on inactive status after a short grace period.

For a small or mid-sized firm, CTAPP compliance should be built into your annual routine (much like MCLE compliance). Mark your calendar for whatever the yearly window is (likely January each year) to log in to the Bar’s system, register your accounts, do the self-assessment quiz, and certify compliance. It’s wise for firm administrators to handle the logistics, but each attorney will need to attest individually. The self-assessment is confidential and not something you submit to the Bar – it’s for your own education – but you still must affirm you completed it.

The advent of CTAPP means the State Bar is far less tolerant of “I didn’t know” or “I forgot” excuses when it comes to trust accounting. Every year you are actively reminded of the rules and required to engage with them. On the positive side, CTAPP is a great prompt for firms to review their trust accounting practices annually and fix any weak spots before they become problems. Consider using the CTAPP self-assessment as an internal audit tool: if any questions gave you pause (e.g. “Are you doing X procedure regularly?”), take that as an opportunity to implement improvements.

Don’t neglect CTAPP. It’s a relatively new hoop to jump through, but it’s now part of doing business as a lawyer in California. By staying ahead of CTAPP deadlines and requirements, you’ll avoid administrative suspension and demonstrate to clients (and the Bar) that you take fiduciary duty seriously.

Best Practices for Trust Accounting (and Avoiding Pitfalls)

Now that we’ve covered the rules, how can you practically adhere to them in a busy law practice? Small and mid-sized firms often juggle multiple roles – your bookkeeper might also be your paralegal, or a partner might be wearing the “accountant” hat after hours. The following best practices will help ensure compliance and prevent the common pitfalls that trap many attorneys:

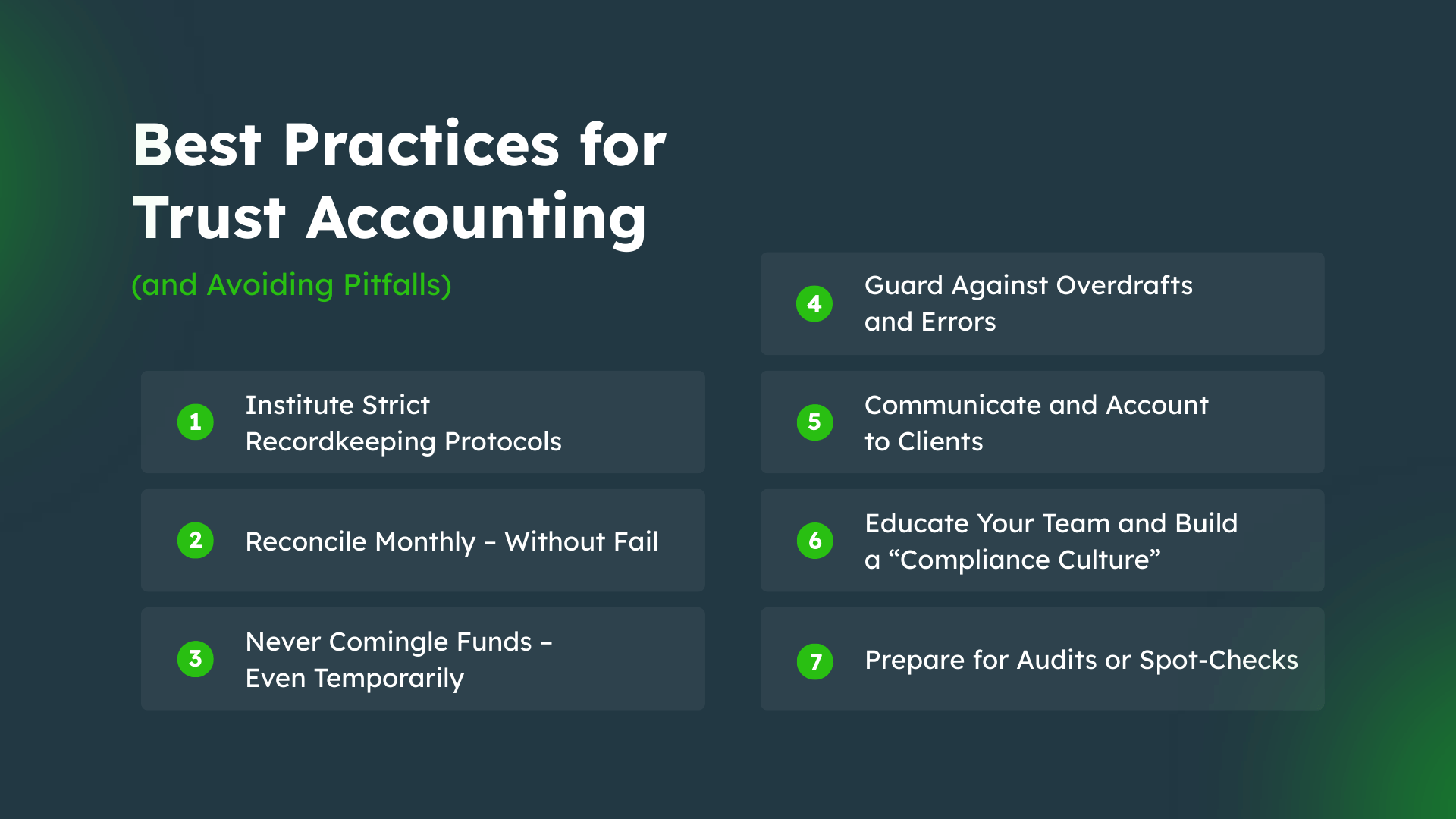

1. Institute Strict Recordkeeping Protocols

Set up a systematic method to record every trust transaction. Ideally, use software (or at least spreadsheets) that are designed for legal trust accounting to maintain the required client ledgers and journals. For each matter where you hold funds, open a ledger and update it immediately whenever money comes in or goes out. Keep electronic (and/or physical) copies of all supporting documents (receipts, invoices, cleared checks).

It’s much easier to maintain records contemporaneously than to reconstruct them later under pressure. California expects you to be able to produce records on demand, so organize them in a logical way (by client and date). If you ever get an audit letter from the Bar, you should be able to pull up bank statements and reconciliation reports for any month requested with minimal effort.

2. Reconcile Monthly – Without Fail

Make it a non-negotiable task that the trust account is reconciled to the penny every month. This means comparing the bank statement to your internal records and resolving any differences. Many small firms designate a specific day, e.g., the first Monday of each month, for trust reconciliation. Treat it like a client deadline. Regular reconciliation will catch errors (like a transaction recorded in the wrong client ledger, or a bank service fee taken out unexpectedly) before they snowball.

It’s also an opportunity to review each client ledger for any balances that have been sitting too long, so you can remind yourself to follow up on disbursing those funds. Document your reconciliations – for instance, sign and date a printout or save a PDF each month – so you have proof of compliance. If the idea of reconciliation sounds tedious, note that good legal accounting software can automate much of this process, alerting you to inconsistencies automatically (more on that in the next section).

3. Never Comingle Funds – Even Temporarily

Commingling is both one of the simplest concepts and one of the easiest ways to mess up. Remember that the trust account is not your money. Don’t borrow from it, even if you plan to pay it back next week. Don’t pay your office bills directly from a trust account. And conversely, don’t deposit personal or firm funds into trust (aside from the token amount for bank fees) because that obscures what amount is truly client money. If you receive a single check that covers multiple things (like a settlement check that reimburses your costs and pays the rest to the client), split it immediately – put the client’s portion in trust, and transfer your portion to the operating account.

Do not leave your portion in trust for convenience. The State Bar has little patience for “innocent” commingling; even if no client is harmed, it’s treated as a serious breach of fiduciary duty. A good internal control is to have at least two people aware of trust balances – for example, one person inputs transactions but a partner regularly reviews the bank balance vs. client ledgers. This oversight makes it harder for inadvertent commingling or mysterious funds to go unnoticed.

4. Guard Against Overdrafts and Errors

As noted, an overdraft will trigger an automatic report to the Bar, so prevention is key. Some preventive measures:

- Keep a fee cushion: deposit a small amount of firm money (permitted for bank charges) and never let the account balance fall below that amount when you’re not actively holding client funds. That way, a surprise bank fee doesn’t put you in the red.

- Use low-balance alerts: Many banks let you set email/text alerts when an account drops below a certain threshold. Set a threshold slightly above $0 (or above your fee cushion amount) to catch any near-overdraft situations.

- No ATM/Debit Cards: It’s wise to disable ATM or debit card access on your trust account. This prevents any chance of someone withdrawing cash or a debit purchase hitting the account. All disbursements should ideally be by check or electronic transfer with proper authorization.

- Dual controls: For additional security, require two signatures on trust checks above a certain amount, or two-person approval for online transfers. This reduces the risk of one person accidentally or intentionally moving funds improperly. In a small firm, this might mean at least one partner’s signature is needed on any check to, say, pay client settlement funds.

- Frequent review: The responsible attorney should review the trust account activity regularly (at least monthly, if not weekly). Initialing the bank statements or having a brief meeting to go over any unusual transactions is a good practice. Remember, ultimate responsibility lies with the attorney in charge of the case funds – staff can help, but you must supervise.

5. Communicate and Account to Clients

Transparency can save you trouble. Periodically update clients on the status of their trust funds, especially for long-term holds. For instance, if you’re holding settlement money pending resolution of liens, you might send the client a brief summary every few months: “Your funds remain in our trust account, in the amount of $X, pending clearance of the Medicare lien.” Not only is this good client service, but it fulfills your duty to account. Also, if a client requests a full accounting of their funds, you must provide it promptly – this is mandated by law.

Being organized with your records (see #1 above) makes this easy. If a client ever questions a trust transaction, respond quickly with documentation. It’s far better to address a client’s concern early than to have them file a complaint because they think something fishy is going on. Proactive communication builds trust and can prevent misunderstandings that lead to grievances.

6. Educate Your Team and Build a “Compliance Culture”

Make sure everyone at your firm who handles client money understands the stakes. Train new associates or staff on the basics of California trust accounting. Emphasize that even a small lapse can have big consequences – not just for the responsible individual, but for the firm’s reputation. It can be helpful to create a simple internal checklist or flowchart for trust transactions (e.g., “Client payment arrives → goes to trust; generate receipt; enter in ledger; on invoice, apply trust funds; when earned, transfer funds…”).

Having a documented procedure ensures consistency. Also, foster a culture where questions are encouraged. If a staff member isn’t sure how to categorize a transaction, they should feel comfortable asking a supervisor or consulting the State Bar’s Client Trust Account Handbook for guidance. Regularly review the State Bar’s resources or ethics opinions on trust accounts – they are there to help you stay compliant. By treating trust accounting as a normal (and important) part of case management rather than an afterthought, your firm is far less likely to run into trouble.

7. Prepare for Audits or Spot-Checks

Even if you never have a complaint, the Bar can audit randomly or due to the CTAPP process. Always be prepared to show that every penny in your trust account is accounted for. One way to test yourself is to pick a client at random and try to produce a full accounting of their funds: starting balance, all inflows, all outflows, ending balance, and where any remaining money went. If you can do that for any client without scrambling, you’re in good shape. Another tip: keep a copy of the monthly three-way reconciliation reports in a safe place.

These are often the first thing an auditor will ask for. If you’re using software, export or print the report each month. If you ever find an error in your records, document when and how you corrected it – showing a paper trail of correction can demonstrate your diligence (for instance, “Discovered $100 bank fee not recorded in March ledger; corrected on April 2 and reimbursed account”). It’s far better to self-correct mistakes than to have an auditor find them with no explanation.

By following these best practices, you’ll greatly reduce the risk of a trust accounting misstep. Yes, it requires diligence, but the peace of mind is worth it – and your clients and regulators will appreciate your professionalism in handling client funds.

How Legal Tech Solutions Like LeanLaw Streamline Trust Accounting

Trust accounting compliance may sound labor-intensive, especially for a small firm without a full-fledged accounting department. This is where leveraging legal technology can be a game-changer. Modern legal practice management and accounting software are designed to take much of the manual work (and human error) out of trust accounting. A prime example is LeanLaw’s trust accounting software, which has features tailored to help law firms meet State Bar requirements with ease.

Automation of Three-Way Reconciliation

One of the most powerful benefits of using dedicated software is automated reconciliation. LeanLaw integrates directly with QuickBooks Online, meaning every transaction in your trust bank account can sync into your accounting system in real time. With continuous syncing, LeanLaw effectively performs three-way reconciliation in the background by keeping your client ledger, your trust account balance in QuickBooks, and the bank records aligned at all times.

Instead of spending hours cross-checking ledgers and bank statements, you can simply generate a reconciliation report through LeanLaw and quickly spot if anything is off. The software can flag discrepancies (for example, if a transaction is in QuickBooks but hasn’t cleared the bank, or vice versa), so you can address them proactively. In short, LeanLaw helps keep your trust accounts “audit-ready” 24/7 – a huge relief when it comes to compliance.

Built-In Compliance Safeguards

LeanLaw’s cloud-based platform is built with state bar trust accounting standards in mind. For instance, it enforces the separation of funds by associating trust deposits and payments with specific client matters. When you receive a retainer, you record it in LeanLaw under the client’s trust account, and the software will track that balance separately from your operating funds.

When you invoice the client and want to apply trust funds to the bill, LeanLaw facilitates the transfer in a compliant way – moving the money from the client’s trust ledger to pay the invoice (which then shows up as revenue in operating). This workflow helps ensure you only withdraw what’s been earned and that there’s a clear record of every transfer. Moreover, LeanLaw prevents common errors like applying more trust funds than the client has on balance (no more accidental overdrafts or negative client ledgers). It essentially won’t let you commingle or overdraw because the rules are baked into the software’s logic.

Automated Record-Keeping and Reporting

Remember those recordkeeping requirements – individual ledgers, journals, etc.? LeanLaw handles much of that automatically. Every client’s trust funds are recorded in a virtual client ledger in the system, and every transaction is time-stamped. You can generate a report at any time for a single client showing all their trust activity and current balance – handy if a client requests an accounting. The software also maintains a running balance for the overall trust account (the equivalent of a check register) and can produce receipts and disbursement journals on demand.

Need to prove your compliance or do your CTAPP self-assessment? Just pull the reports for a given period. LeanLaw even offers trust-specific reports like “Three-way Reconciliation” that display the bank balance, list of client balances, and any differences, making monthly reviews straightforward. By automating record creation and keeping everything organized, the software reduces the risk of human error – no more forgotten entries or arithmetic mistakes that could put you out of balance.

Streamlined Client Payments and Transfers

Legal tech solutions can also simplify the process of getting money in and out of trust properly. For example, LeanLaw integrates with electronic payment systems (through its LeanLaw Payments or partner integrations) so that clients can pay retainers or replenish trust funds online. Those payments can go directly into your IOLTA account and are automatically recorded to the correct client ledger.

This saves you from manually depositing checks and keying in data. On the disbursement side, when it’s time to use trust funds (say, paying a filing fee or sending settlement money to a client), you can initiate that through the software, which will record the transaction and even generate checks or electronic transfers with the proper notations. By using a system that is purpose-built for law firm trust accounting, each step is tracked and properly labeled, greatly reducing the chance of compliance slip-ups.

Real-Time Visibility and Alerts

Another advantage of software like LeanLaw is the dashboard visibility. At any given moment, you can see a summary of your trust account status – how much total is in trust and a breakdown by client. This real-time insight helps you manage funds more effectively. If a client’s balance is running low (perhaps a retainer that’s nearly exhausted), LeanLaw can alert you so you can ask the client to replenish before it’s fully depleted.

Some tools also offer notifications if something unusual occurs, like a check clears that wasn’t entered, etc. Essentially, you have constant eyes on the trust account without needing to log into the bank or update spreadsheets constantly. This is especially helpful for busy attorneys who can’t afford to micromanage the account daily.

Seamless Integration with Billing & Accounting

Small and mid-sized firms benefit when their billing, accounting, and trust management systems talk to each other. LeanLaw is an example of a solution that connects trust accounting with your general accounting (QuickBooks) and time billing. When you invoice a client, LeanLaw can automatically apply any trust funds to the invoice (with your approval) and show the remaining trust balance. It will generate the necessary accounting entries in QuickBooks to reflect that the funds moved from the trust liability to income – all behind the scenes.

This level of integration means no duplicate data entry, which is a common source of mistakes. By eliminating redundant steps, LeanLaw not only saves time but also ensures consistency: the number in your trust bank account will match the number in your books and in your client statements. In an audit, that consistency is your best friend.

Audit Trails and Security

Every action taken in LeanLaw (or similar software) leaves an audit trail. If multiple people in your firm handle trust funds, the software will log who did what – providing accountability. Role-based permissions can be set so that, for instance, a paralegal can record a deposit but maybe not authorize a withdrawal without a supervisor. This builds internal controls through technology. Additionally, having data in the cloud (with proper backups) means even if physical records are lost or a hard drive crashes, your trust accounting records are preserved – an important consideration for disaster recovery compliance.

In essence, legal tech solutions act as a fiduciary safety net. They enforce rules and arithmetic that humans might otherwise skip under pressure. For a California firm, a tool like LeanLaw can handle the heavy lifting of compliance – maintaining those detailed ledgers and reports that the State Bar wants to see – while you focus on your clients’ cases. By streamlining trust accounting, you reduce the risk of error, save valuable administrative time, and gain peace of mind that you’re “doing it right.”

LeanLaw’s platform, for example, was designed with input from attorneys and accountants to meet the nuanced requirements of trust accounting. It offers features like one-click three-way reconciliation, automatic bank feed imports, trust balance dashboards, and built-in CTAPP compliance support – all of which can be especially beneficial for small and mid-sized firms that don’t have dedicated accounting staff. As a result, even a solo practitioner can manage a trust account like a pro, with confidence that nothing will fall through the cracks.

Conclusion

Trust accounting is often cited as one of the most challenging administrative tasks for law firms – but it doesn’t have to intimidate you. By understanding California’s specific rules and incorporating solid workflows, small and mid-sized law firms can master trust accounting just as well as any big firm. Remember that compliance in this area is non-negotiable: the stakes are simply too high, from client welfare to your license to practice. Thankfully, California’s State Bar provides resources (like the Client Trust Accounting Handbook and CTAPP self-assessment tools) to guide you, and modern software solutions are available to automate much of the process.

In practice, successful trust accounting in a California law firm boils down to a few fundamental habits: keep client money separate, document everything, reconcile often, and never ignore an issue. If you commit to these principles – and leverage technology like LeanLaw to assist – you’ll greatly minimize the risk of ever hearing from the Bar about a trust discrepancy. Instead, you can confidently assure your clients that their funds are safe and sound, and direct your energy where it truly belongs: advocating for your clients, not poring over spreadsheets.

By implementing the guidance in this article, you’re not only protecting your firm from compliance trouble; you’re also building trust with your clients through financial transparency and reliability. In the end, diligent trust accounting is part of running a lean, professional, and ethical law practice. So take the steps now to tighten up your trust procedures and consider tools that can lighten the load. With the right approach, even California’s rigorous trust accounting rules can be managed smoothly – keeping your firm in good standing and your client relationships strong.